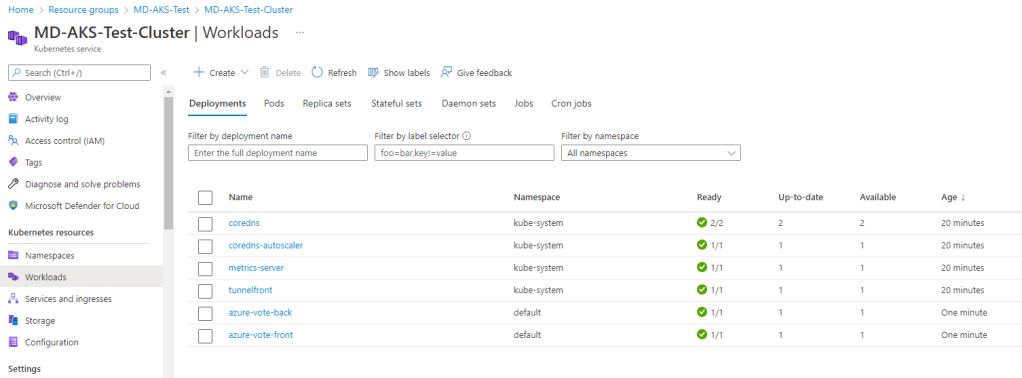

In the previous post, we broke down AKS Architecture Fundamentals — control plane vs data plane, node pools, availability zones, and early production guardrails.

Now we move into one of the most consequential design areas in any AKS deployment:

Networking.

If node pools define where workloads run, networking defines how they communicate — internally, externally, and across environments.

Unlike VM sizes or replica counts, networking decisions are difficult to change later. They shape IP planning, security boundaries, hybrid connectivity, and how your platform evolves over time.

This post takes a look at AKS networking by exploring:

- The modern networking options available in AKS

- Trade-offs between Azure CNI Overlay and Azure CNI Node Subnet

- How networking decisions influence node pool sizing and scaling

- How the control plane communicates with the data plane

Why Networking in AKS Is Different

With traditional Iaas and PaaS services in Azure, networking is straightforward: a VM or resource gets an IP address in a subnet.

With Kubernetes, things become layered:

- Nodes have IP addresses

- Pods have IP addresses

- Services abstract pod endpoints

- Ingress controls external access

AKS integrates all of this into an Azure Virtual Network. That means Kubernetes networking decisions directly impact:

- IP address planning

- Subnet sizing

- Security boundaries

- Peering and hybrid connectivity

In production, networking is not just connectivity — it’s architecture.

The Modern AKS Networking Choices

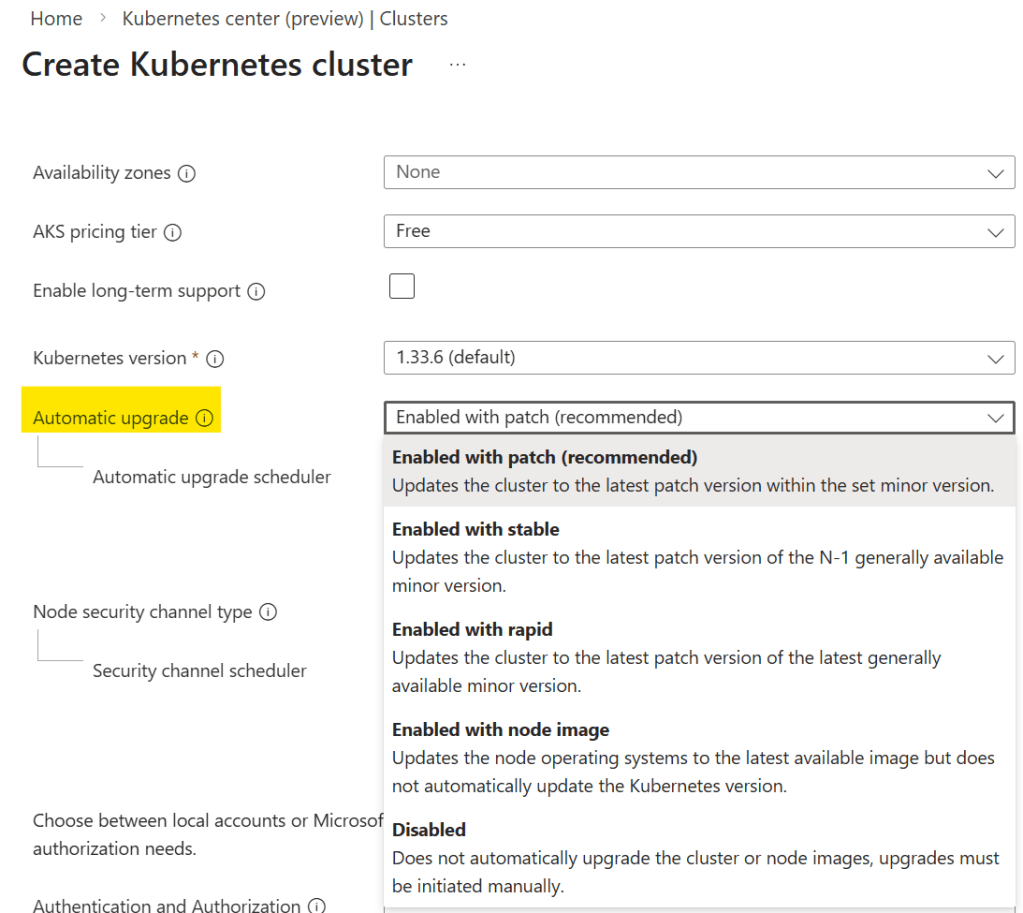

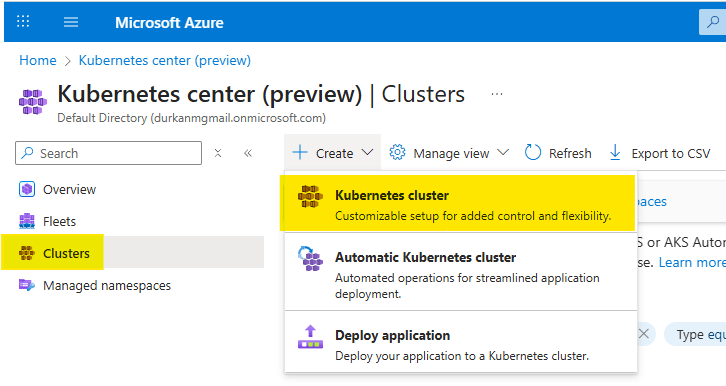

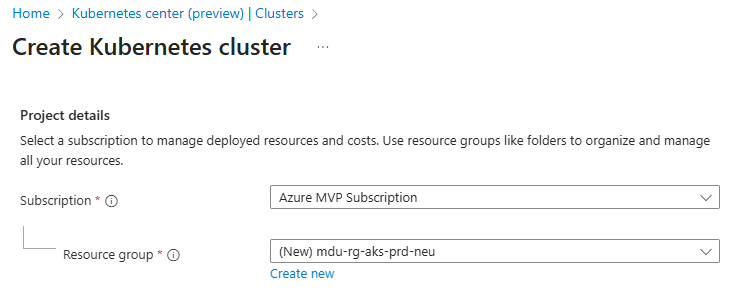

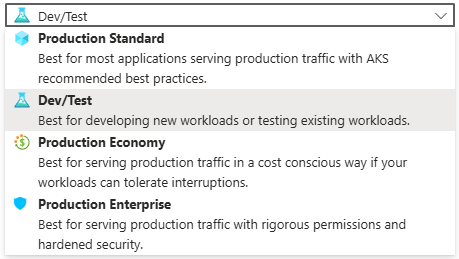

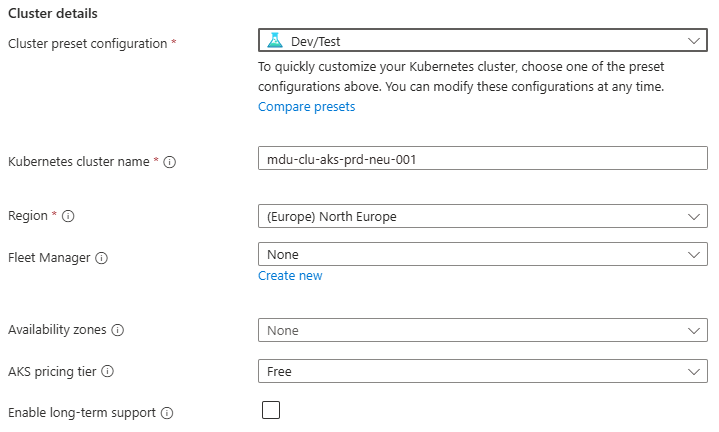

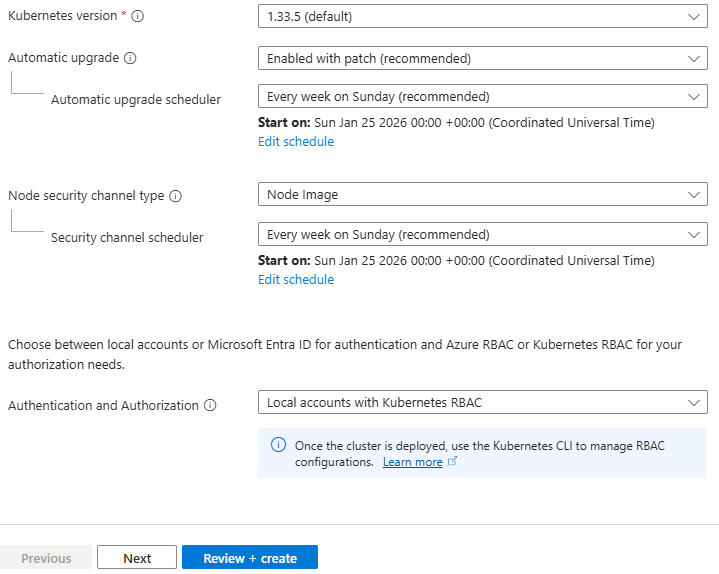

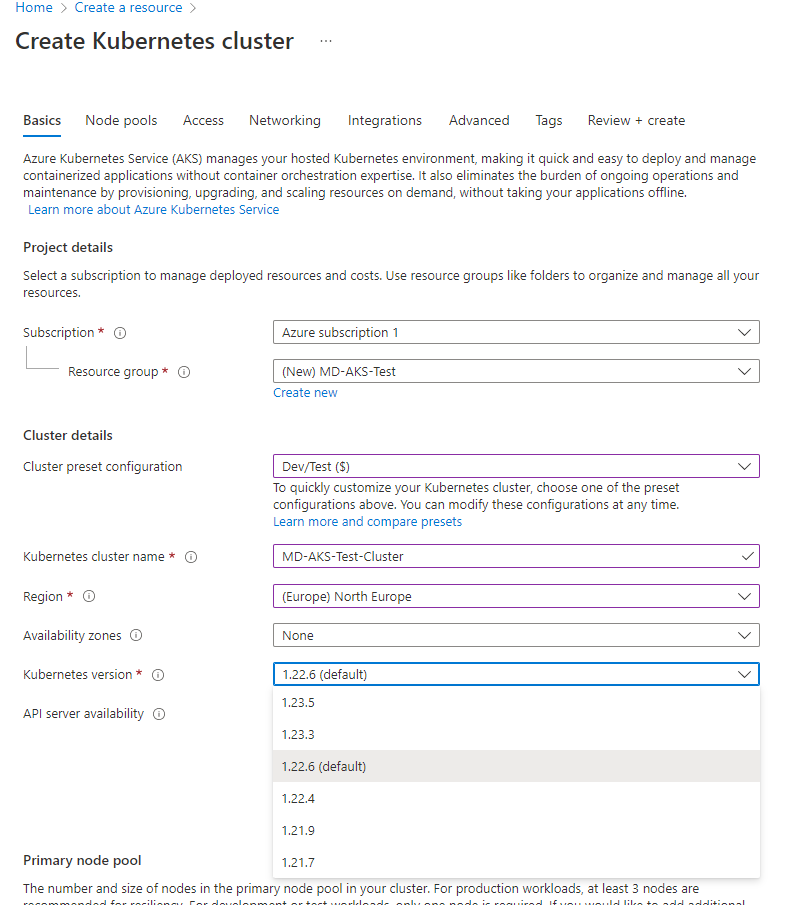

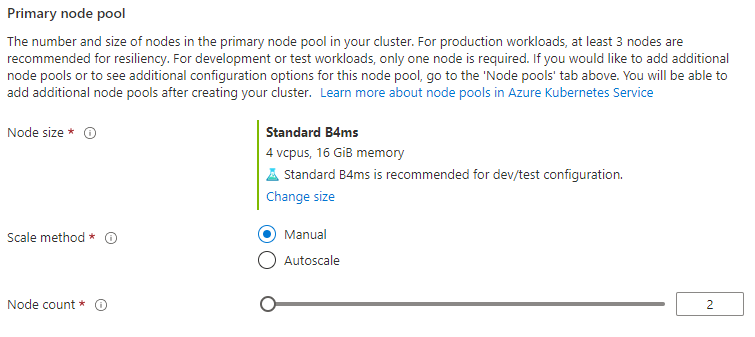

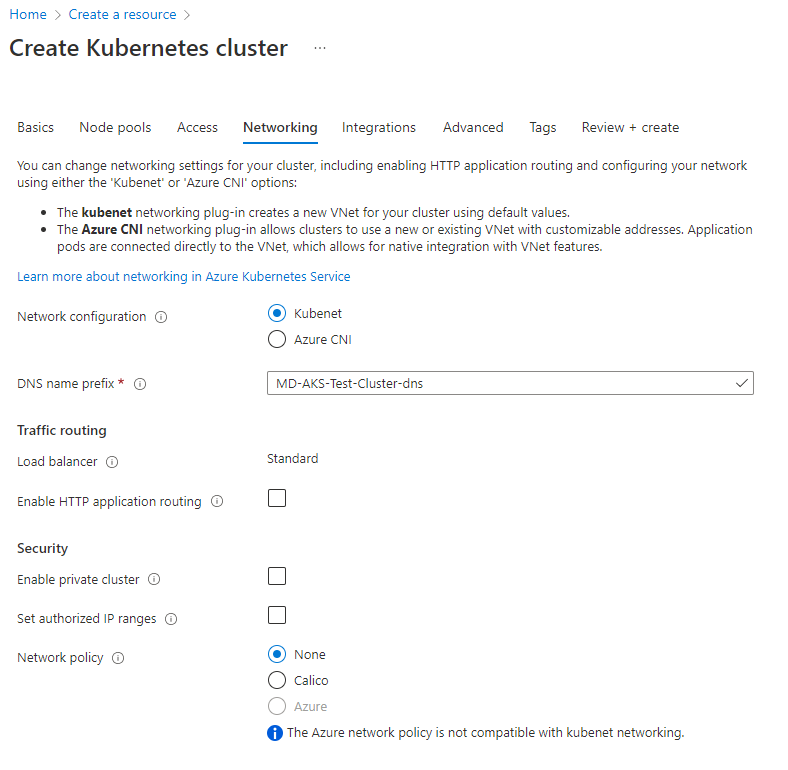

Although there are some legacy models still available for use, if you try to deploy an AKS cluster in the Portal you will see that AKS offers two main networking approaches:

- Azure CNI Node Subnet (flat network model)

- Azure CNI Overlay (pod overlay networking)

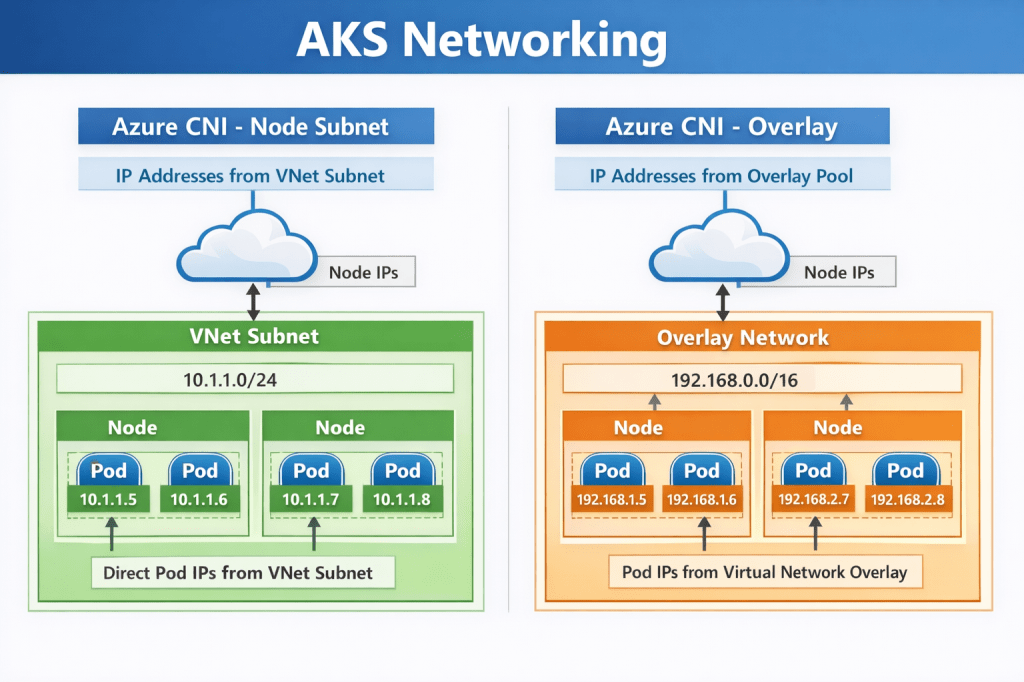

As their names suggest, both use Azure CNI. The difference lies in how pod IP addresses are assigned and routed. Understanding this distinction is essential before you size node pools or define scaling limits.

Azure CNI Node Subnet

This is the traditional Azure CNI model.

Pods receive IP addresses directly from the Azure subnet. From the network’s perspective, pods appear as first-class citizens inside your VNet.

How It Works

Each node consumes IP addresses from the subnet. Each pod scheduled onto that node also consumes an IP from the same subnet. Pods are directly routable across VNets, peered networks, and hybrid connections.

This creates a flat, highly transparent network model.

Why teams choose it

This model aligns naturally with enterprise networking expectations. Security appliances, firewalls, and monitoring tools can see pod IPs directly. Routing is predictable, and hybrid connectivity is straightforward.

If your environment already relies on network inspection, segmentation, or private connectivity, this model integrates cleanly.

Pros

- Native VNet integration

- Simple routing and peering

- Easier integration with existing network appliances

- Straightforward hybrid connectivity scenarios

- Cleaner alignment with enterprise security tooling

Cons

- High IP consumption

- Requires careful subnet sizing

- Can exhaust address space quickly in large clusters

Trade-offs to consider

The trade-off is IP consumption. Every pod consumes a VNet IP. In large clusters, address space can be exhausted faster than expected. Subnet sizing must account for:

- node count

- maximum pods per node

- autoscaling limits

- upgrade surge capacity

This model rewards careful planning and penalises underestimation.

Impact on node pool sizing

With Node Subnet networking, node pool scaling directly consumes IP space.

If a user node pool scales out aggressively and each node supports 30 pods, IP usage grows rapidly. A cluster designed for 100 nodes may require thousands of available IP addresses.

System node pools remain smaller, but they still require headroom for upgrades and system pod scheduling.

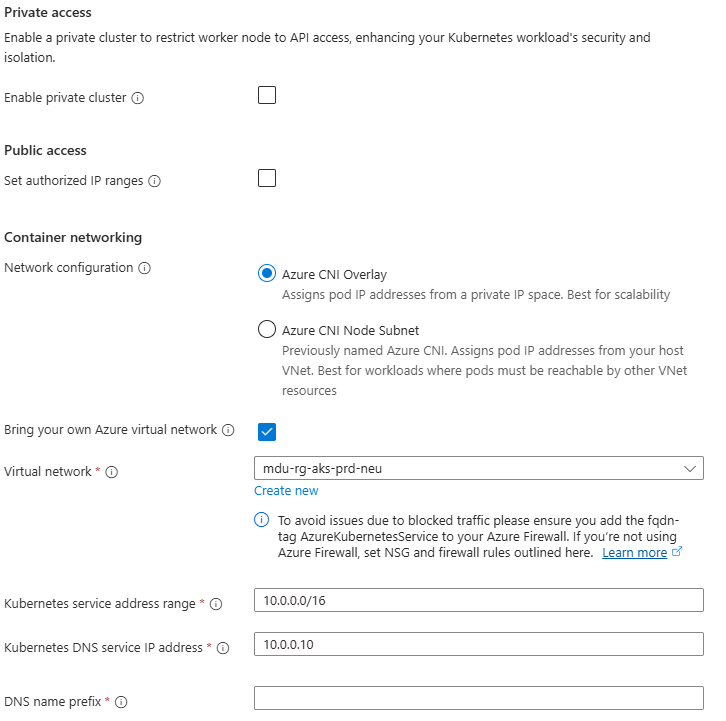

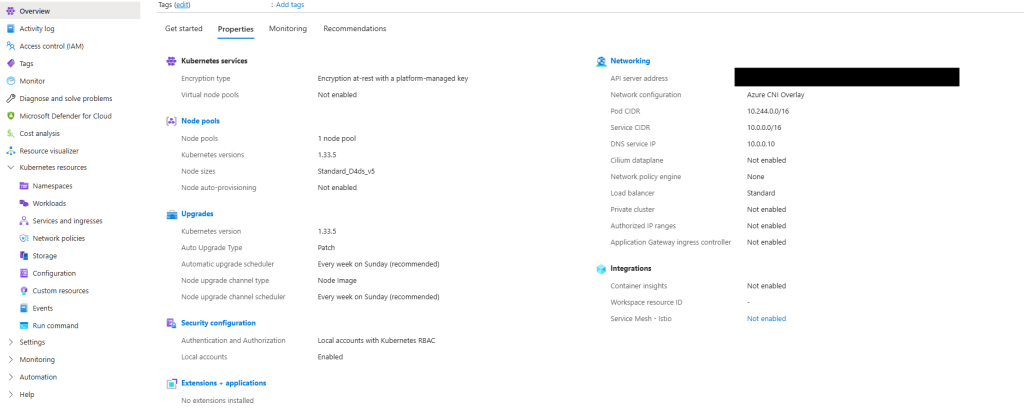

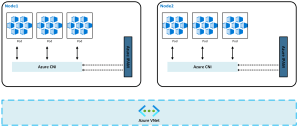

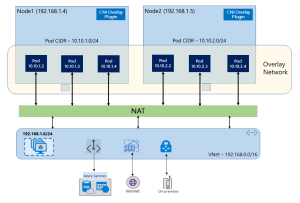

Azure CNI Overlay

Azure CNI Overlay is designed to address IP exhaustion challenges while retaining Azure CNI integration.

Pods receive IP addresses from an internal Kubernetes-managed range, not directly from the Azure subnet. Only nodes consume Azure VNet IP addresses.

How It Works

Nodes are addressable within the VNet. Pods use an internal overlay CIDR range. Traffic is routed between nodes, with encapsulation handling pod communication.

From the VNet’s perspective, only nodes consume IP addresses.

Why teams choose it

Overlay networking dramatically reduces pressure on Azure subnet address space. This makes it especially attractive in environments where:

- IP ranges are constrained

- multiple clusters share network space

- growth projections are uncertain

It allows clusters to scale without re-architecting network address ranges.

Pros

- Significantly lower Azure IP consumption

- Simpler subnet sizing

- Useful in environments with constrained IP ranges

Cons

- More complex routing

- Less transparent network visibility

- Additional configuration required for advanced scenarios

- Not ideal for large-scale enterprise integration

Trade-offs to consider

Overlay networking introduces an additional routing layer. While largely transparent, it can add complexity when integrating with deep packet inspection, advanced network appliances, or highly customised routing scenarios.

For most modern workloads, however, this complexity is manageable and increasingly common.

Impact on node pool sizing

Because pods no longer consume VNet IP addresses, node pool scaling pressure shifts away from subnet size. This provides greater flexibility when designing large user node pools or burst scaling scenarios.

However, node count, autoscaler limits, and upgrade surge requirements still influence subnet sizing.

Choosing Between Overlay and Node Subnet

Here are the “TLDR” considerations when you need to make the choice of which networking model to use:

- If deep network visibility, firewall inspection, and hybrid routing transparency are primary drivers, Node Subnet networking remains compelling.

- If address space constraints, growth flexibility, and cluster density are primary concerns, Overlay networking provides significant advantages.

- Most organisations adopting AKS at scale are moving toward overlay networking unless specific networking requirements dictate otherwise.

How Networking Impacts Node Pool Design

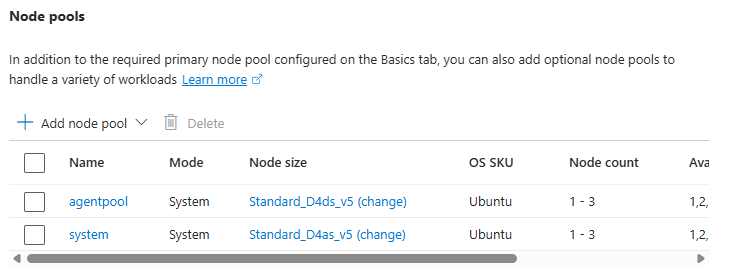

Let’s connect this back to the last post, where we said that Node pools are not just compute boundaries — they are networking consumption boundaries.

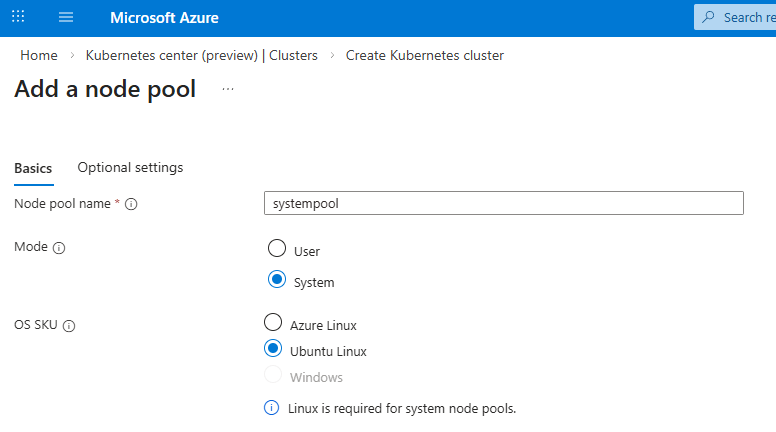

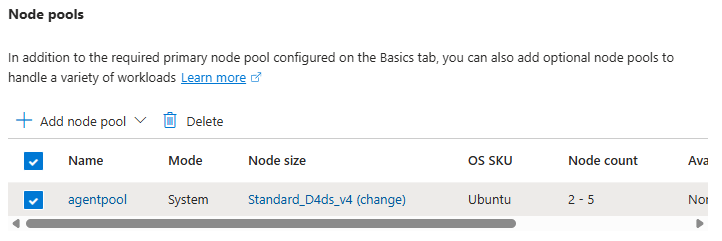

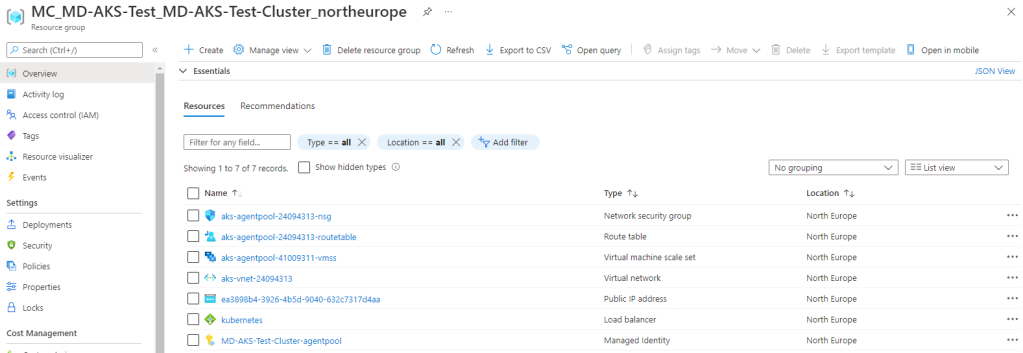

System Node Pools

System node pools:

- Host core Kubernetes components

- Require stability more than scale

From a networking perspective:

- They should be small

- They should be predictable in IP consumption

- They must allow for upgrade surge capacity

If using Azure CNI, ensure sufficient IP headroom for control plane-driven scaling operations.

User Node Pools

User node pools are where networking pressure increases. Consider:

- Maximum pods per node

- Horizontal Pod Autoscaler behaviour

- Node autoscaling limits

In Azure CNI Node Subnet environments, every one of those pods consumes an IP. If you design for 100 nodes with 30 pods each, that is 3,000 pod IPs — plus node IPs. Subnet planning must reflect worst-case scale, not average load.

In Azure CNI Overlay environments, the pressure shifts away from Azure subnets — but routing complexity increases.

Either way, node pool design and networking are a single architectural decision, not two separate ones.

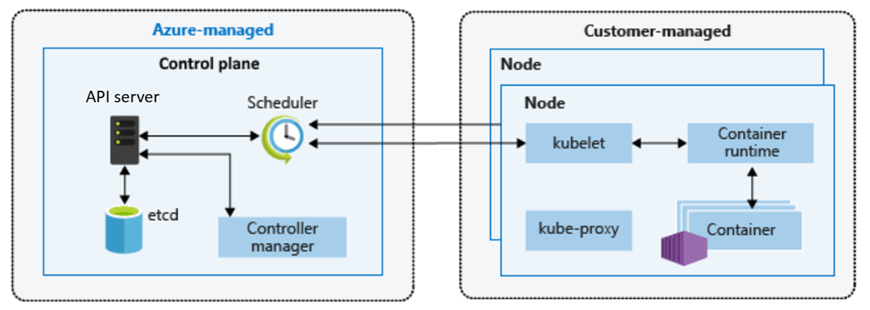

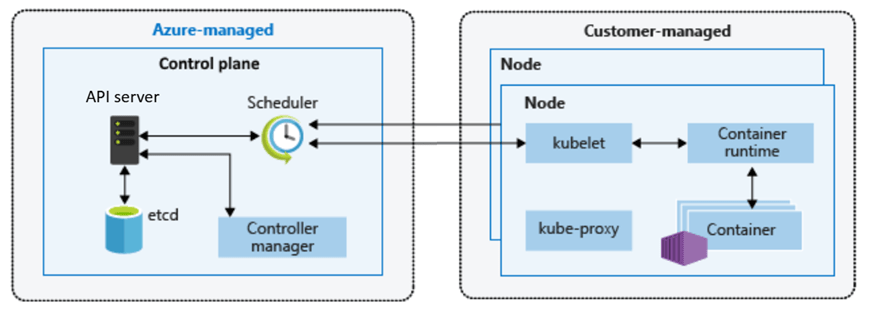

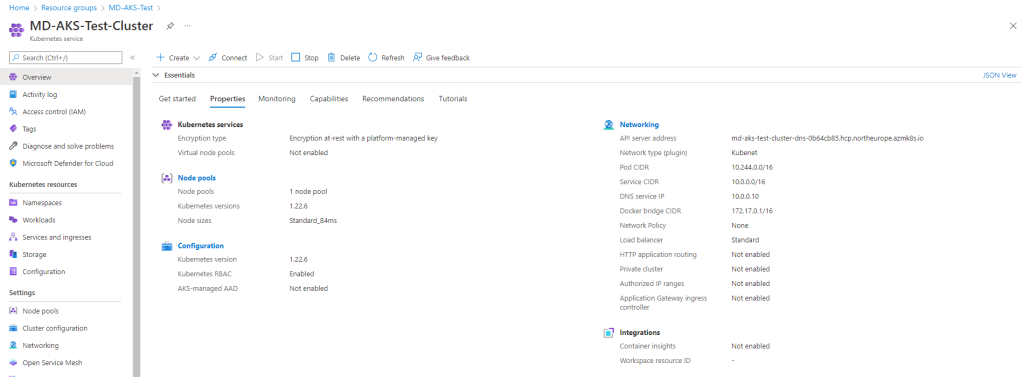

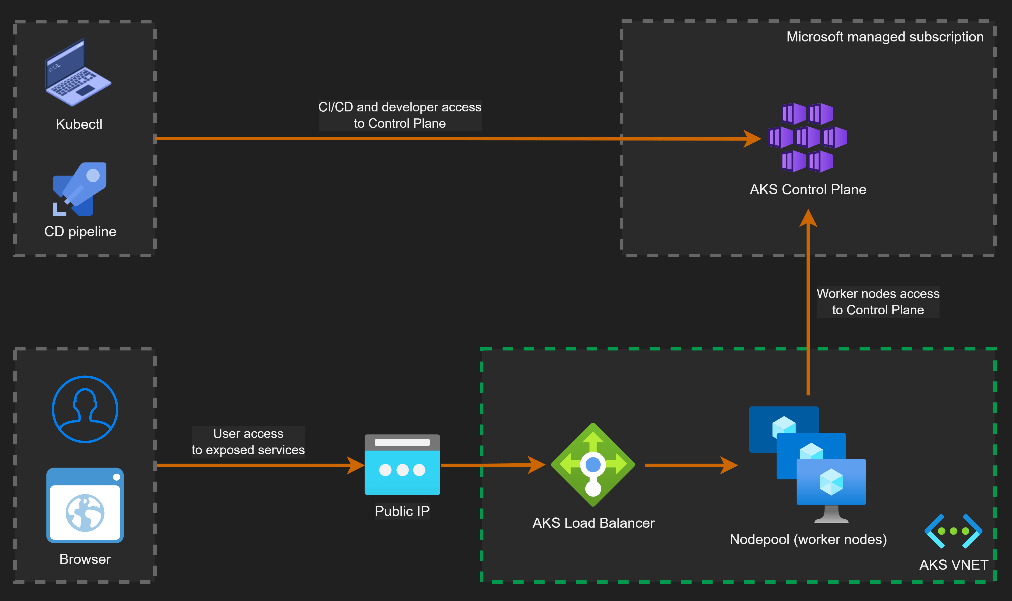

Control Plane Networking and Security

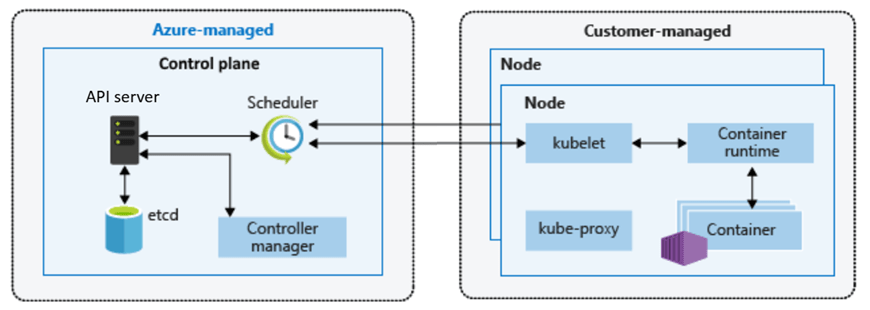

One area that is often misunderstood is how the control plane communicates with the data plane, and how administrators securely interact with the cluster.

The Kubernetes API server is the central control surface. Every action — whether from kubectl, CI/CD pipelines, GitOps tooling, or the Azure Portal — ultimately flows through this endpoint.

In AKS, the control plane is managed by Azure and exposed through a secure endpoint. How that endpoint is exposed defines the cluster’s security posture.

Public Cluster Architecture

By default, AKS clusters expose a public API endpoint secured with authentication, TLS, and RBAC.

This does not mean the cluster is open to the internet. Access can be restricted using authorized IP ranges and Azure AD authentication.

Key characteristics:

- API endpoint is internet-accessible but secured

- Access can be restricted via authorized IP ranges

- Nodes communicate outbound to the control plane

- No inbound connectivity to nodes is required

This model is common in smaller environments or where operational simplicity is preferred.

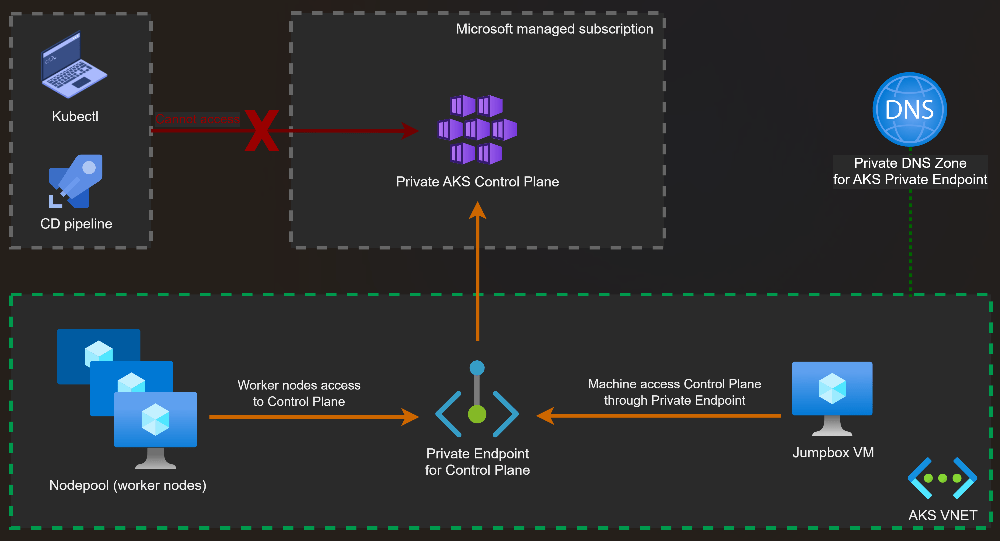

Private Cluster Architecture

In a private AKS cluster, the API server is exposed via a private endpoint inside your VNet.

Administrative access requires private connectivity such as:

- VPN

- ExpressRoute

- Azure Bastion or jump hosts

Key characteristics:

- API server is not exposed to the public internet

- Access is restricted to private networks

- Reduced attack surface

- Preferred for regulated or enterprise environments

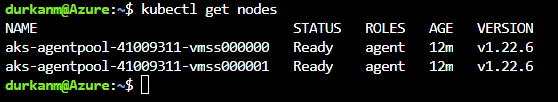

Control Plane to Data Plane Communication

Regardless of public or private mode, communication between the control plane and the nodes follows the same secure pattern.

The kubelet running on each node establishes an outbound, mutually authenticated connection to the API server.

This design has important security implications:

- Nodes do not require inbound internet exposure

- Firewall rules can enforce outbound-only communication

- Control plane connectivity remains encrypted and authenticated

This outbound-only model is a key reason AKS clusters can operate securely inside tightly controlled network environments.

Common Networking Pitfalls in AKS

Networking issues rarely appear during initial deployment. They surface later when scaling, integrating, or securing the platform. Typical pitfalls include:

- subnets sized for today rather than future growth

- no IP headroom for node surge during upgrades

- lack of outbound traffic control

- exposing the API server publicly without restrictions

Networking issues rarely appear on day one. They appear six months later — when scaling becomes necessary.

Aligning Networking with the Azure Well-Architected Framework

- Operational Excellence improves when networking is designed for observability, integration, and predictable growth.

- Reliability depends on zone-aware node pools, resilient ingress, and stable outbound connectivity.

- Security is strengthened through private clusters, controlled egress, and network policy enforcement.

- Cost Optimisation emerges from correct IP planning, right-sized ingress capacity, and avoiding rework caused by subnet exhaustion.

Making the right (or wrong) networking decisions in the design phase has an effect across each of these pillars.

What Comes Next

At this point in the series, we now understand:

- Why Kubernetes exists

- How AKS architecture is structured

- How networking choices shape production readiness

In the next post, we’ll stay on the networking theme and take a look at Ingress and Egress traffic flows. See you then!