Its Day 46 of my 100 Days of Cloud Journey, and today I’m looking at Azure Well Architected Framework.

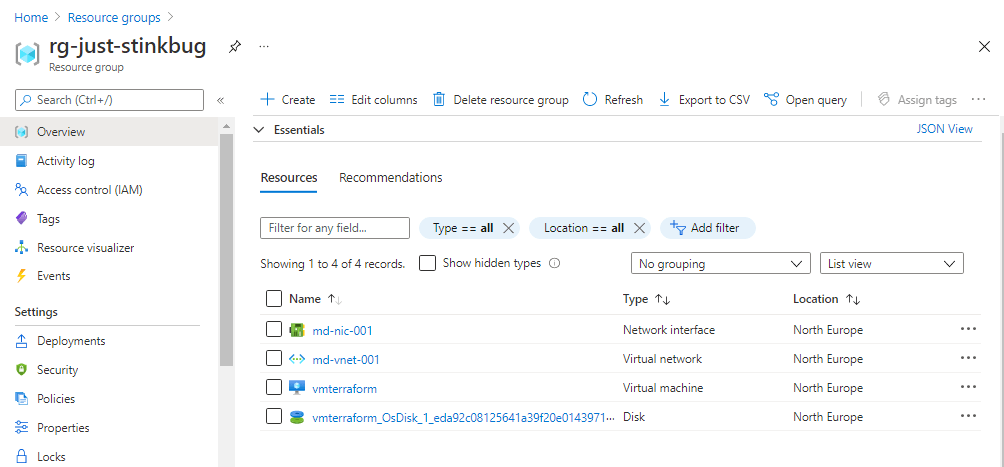

Over the course of my 100 Days journey so far, we’ve talked about and deployed multiple different types of Azure resources such as Virtual Machines, Network Security groups, VPNs, Firewalls etc.

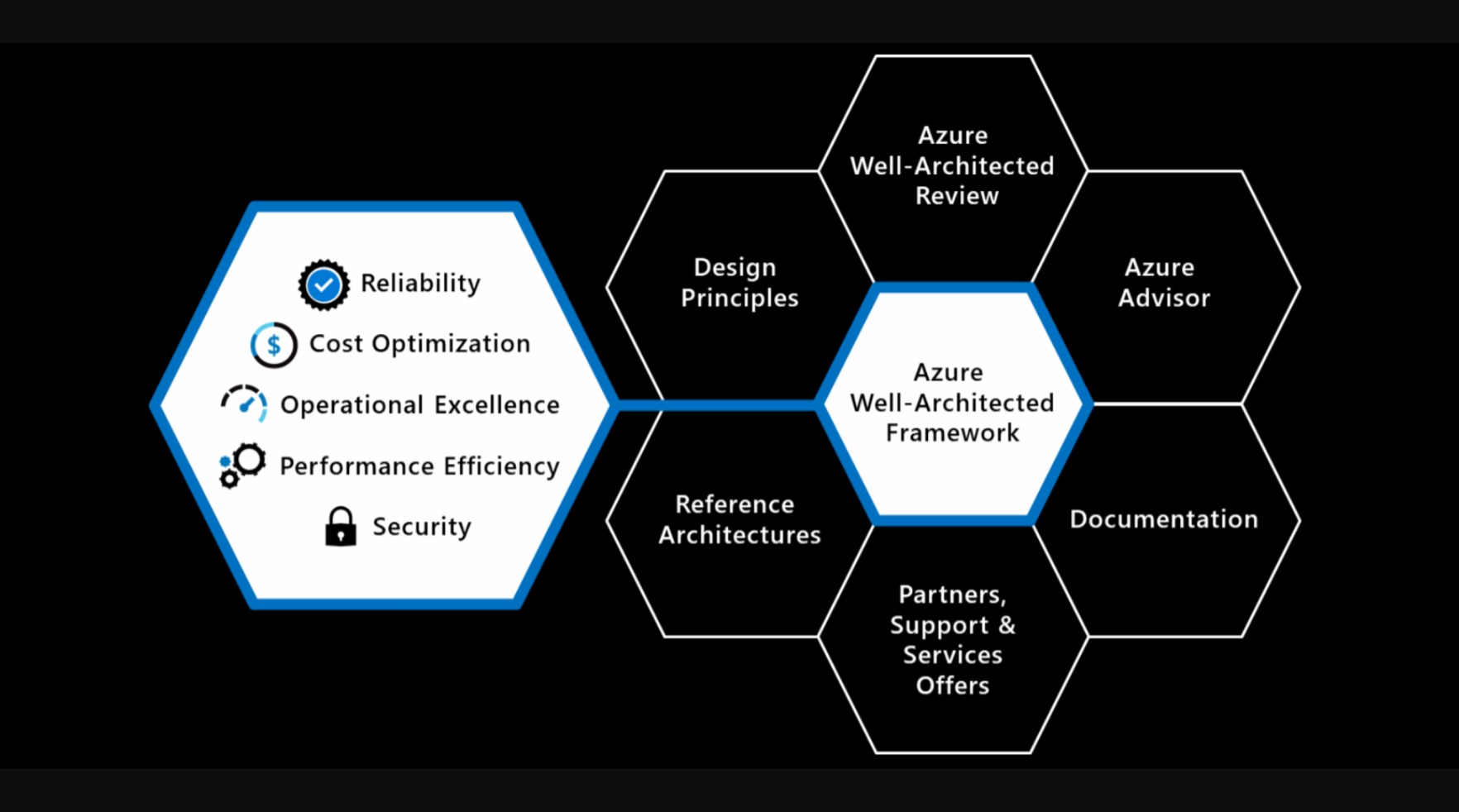

We’ve seen how easy this is to do on a Dev-based PAYG subscription like I’m using, however for companies who wish to migrate to Azure, Microsoft provides a ‘Well Architected Framework’ which offers guidance in ensuring that any resource or solution that is deployed or architected in Azure conforms to best practices around planning, design, implementation and on-going maintenance and improvement of the solution.

The Well Architected Framework is based on 5 key pillars:

- Reliability – this is the ability of a system to recover from failures and continue to function, which in itself is built around 2 key values:

- Resiliency, which returns the application to a fully functional state after a failure.

- Availability, which defines whether users can access the workload if they need to.

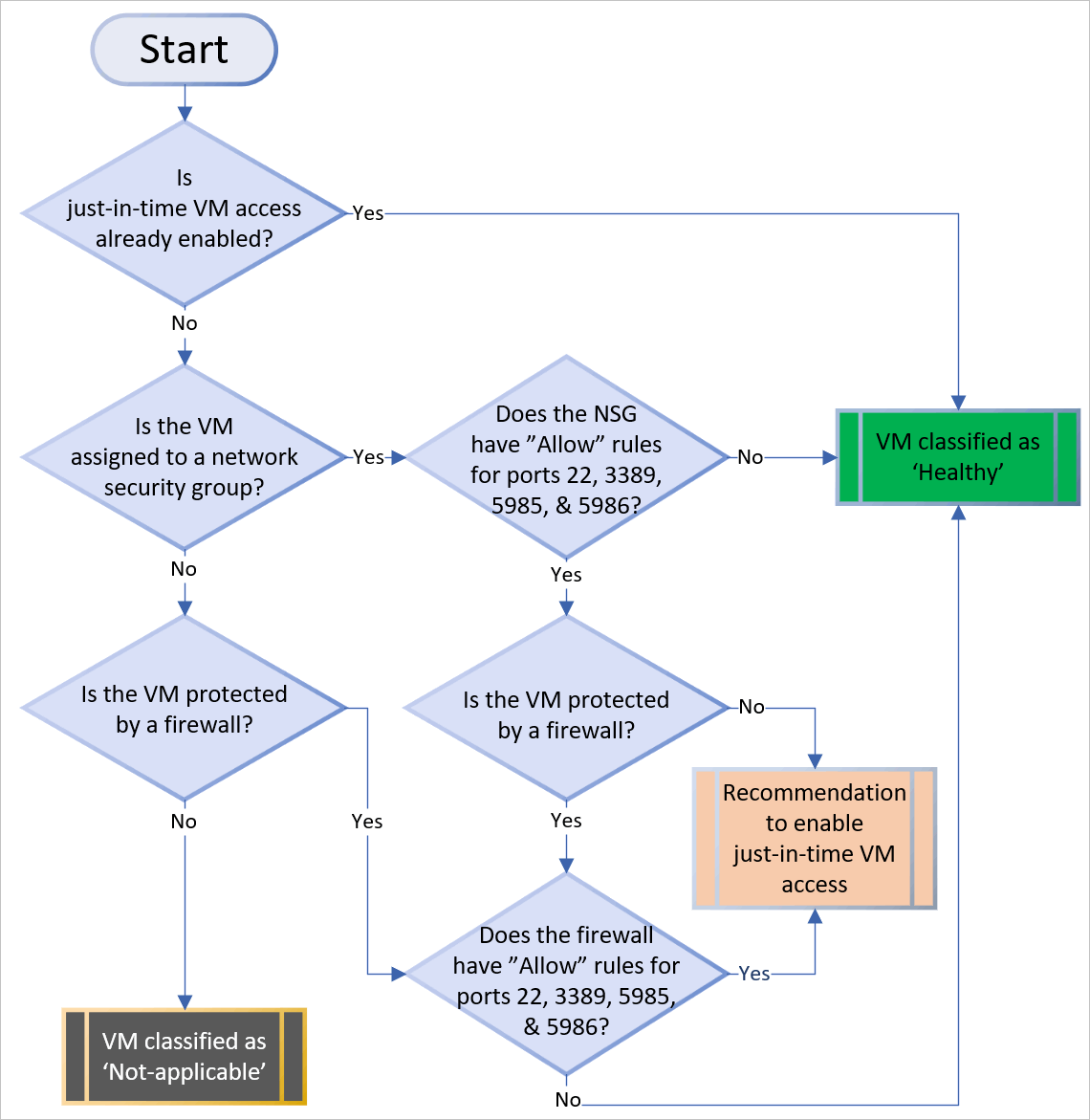

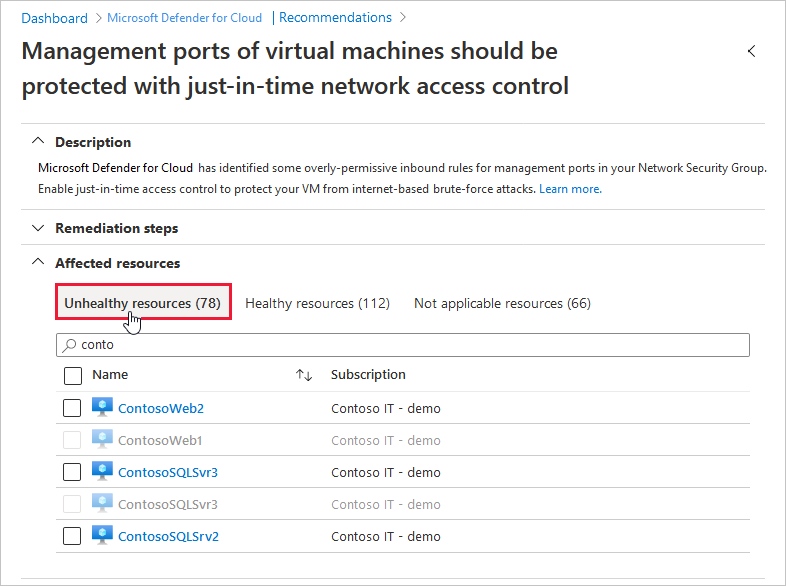

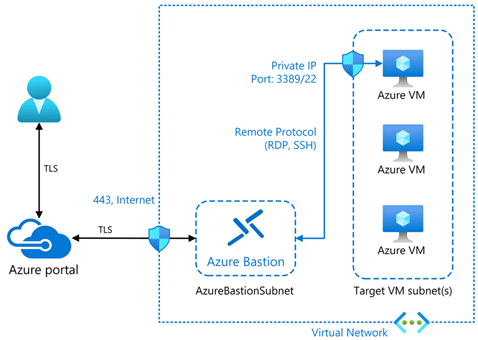

- Security – protects applications and data from threats. The first thing people would think of here is “firewalls”, which would protects against threats and DDoS attacks but its not that simple. We need to build security into the application from the ground up. To do this, we can use the following areas:

- Identity Management, such as RBAC roles and System Managed Identities.

- Application Security, such as storing application secrets in Azure Key Vault.

- Data sovereignty and encryption, which ensures the resource or workload and its underlying data is stored in the correct region and is encrypted using industry standards.

- Security Resources, using tools such as Microsoft Dender for Cloud or Azure Firewall.

- Cost Optimization – managing costs to maximize the value delivered. This can be achieved in the form of using tools such as:

- Azure Cost Management to create budgets and cost alerts

- Azure Migrate to assess the system load generated by your on-premise workloads to ensure thay are correctly sized in the cloud.

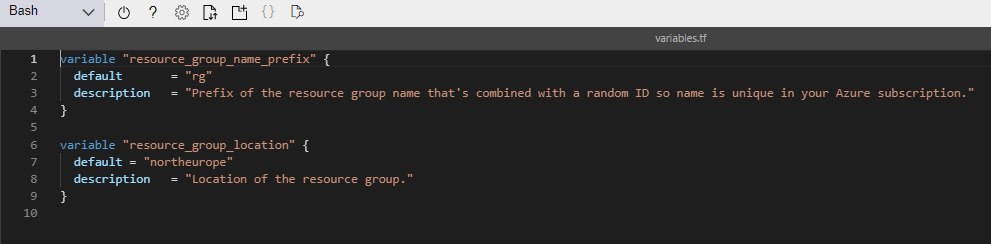

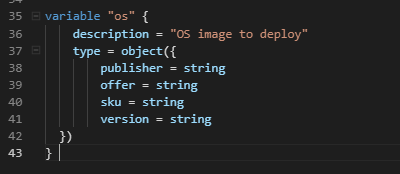

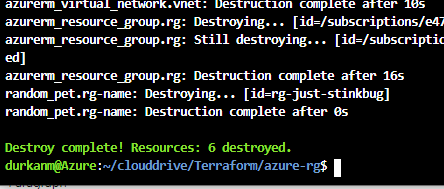

- Operational Excellence – processes that keep a system running in production. In most cases, automated deployments leave little room for human error, and can not only be deployed quickly but can also be rolled back in the event of errors or failures.

- Performance Efficiency – this is the ability of a system to adapt to changes in load. For this, we can think of tools and methodologioes such as auto-scaling, caching, data partitioning, network and storage optimization, and CDN resources in order to make sure your workloads run efficiently.

On top of all this, the Well Architected Framework has six supporting elements wrapped around it:

- Azure Well-Architected Review

- Azure Advisor

- Documentation

- Partners, Support, and Services Offers

- Reference Architectures

- Design Principles

Azure Advisor in particular helps you follow best practises by analyzing your deployments and configuration and provides recommends solutions that can help you improve the reliability, security, cost effectiveness, performance, and operational excellence of your Azure resources. You can learn more about Azure Advisor here.

I recommend anyone who is either in the process of migration or planning to start on their Cloud Migration journey to review the Azure Well Architected Framework material to understand options and best practices when designing and developing an Azure solution. You can find the landing page for Well Architected Framework here, and the Assessments page to help on your journey is here!

Hope you all enjoyed this post, until next time!