Day 14 of 100 Days of Cloud, and today it’s a brief post on Azure Managed Identities.

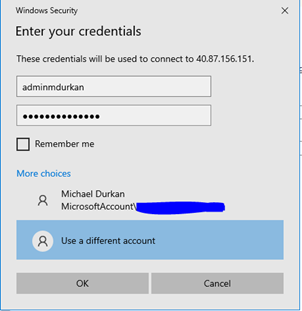

One of the most common challenges for both developers and Infrastructure admins is the ability to store secrets/credentials/passwords which are needed to authenticate to different components in a solution.

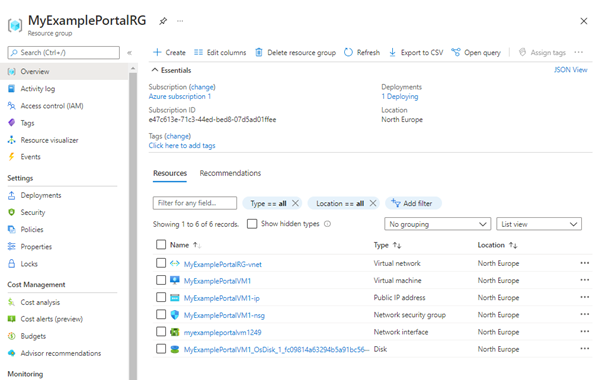

Let’s take a look at a traditional example — you have a 2 Windows Servers running as VMs. One VM hosts a Web Portal where customers can place orders. The second VM hosts the backend SQL Database which holds data for the front end application. As a best practice, there are separate service accounts and passwords in use with administrative permissions for each of the layers of the solution:

- Operating System

- Web Application

- Database

Now, let’s add another layer of complexity. There are 3 different teams that manage each part of the solution.

During a planned upgrade, one of the Web Developers needs to get an urgent change made and makes the error of embedding a password into the code. 2 months later during an audit, all passwords for the solution are changed. But the developer’s recent change suddenly stops working, taking down the entire site!

We’ve all seen this pain happen many times. On-premise, this would normally be solved using the likes of a shared password vault, but the developers still need to manage credentials.

In Azure, this is solved by using Managed Identities.

Overview of Managed Identities

Managed identities in Azure provide an Azure AD identity to an Azure managed resource. Once that resource has an identity, it can work with anything that supports Azure AD authentication.

Let’s move our example above to Azure. This time, we have an Azure VM which runs the Web Portal Service, and an Azure SQL Database Instance storing the Data.

Because the Azure SQL Database supports Azure Active Directory Authentication, we can enable Managed Identity on the VM and grant this permissions to authenticate to the Azure SQL Database. This means that there is no credential management required.

The benefits of using Managed Identities:

- No more management of credentials.

- Can be used to authenticate to any resource that supports Azure Active Directory.

- It’s free!!

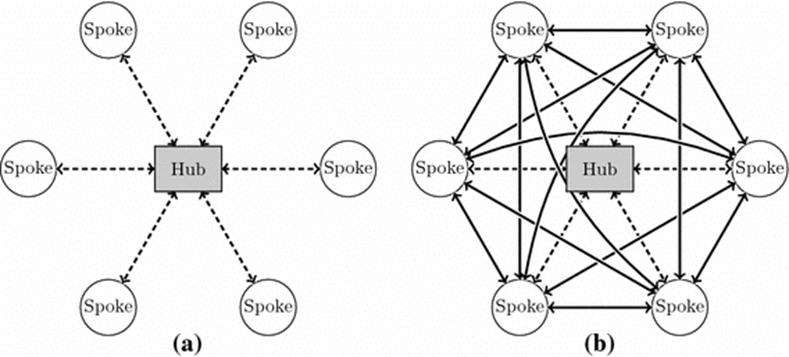

There are 2 types of Managed Identity:

- System-assigned: When you enable a system-assigned managed identity an identity is created in Azure AD that is tied to the lifecycle of that service instance. So when the resource is deleted, Azure automatically deletes the identity for you. By design, only that Azure resource can use this identity to request tokens from Azure AD. In our example above, we would assign the Managed Identity to the Azure SQL Database. If that Database was ever deleted, the Managed Identity would automatically be deleted.

- User-assigned: You may also create a managed identity as a standalone Azure resource. You can create a user-assigned managed identity and assign it to one or more instances of an Azure service. In the case of user-assigned managed identities, the identity is managed separately from the resources that use it.

A full list of services that support managed identities for Azure can be found here.

Let’s jump into a Demo and see how this works.

Creating a VM with a System Managed Identity

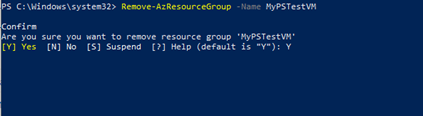

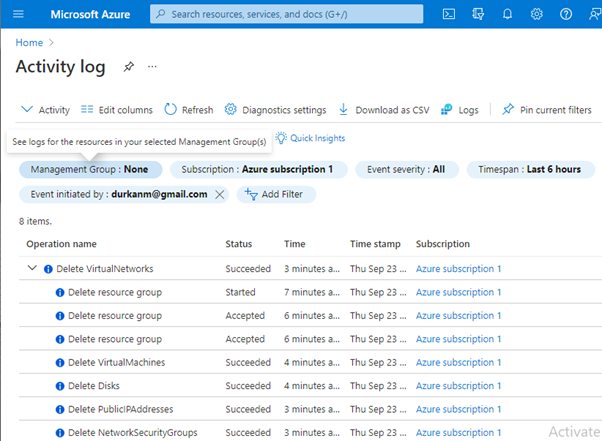

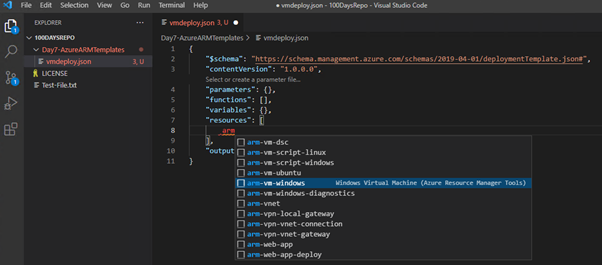

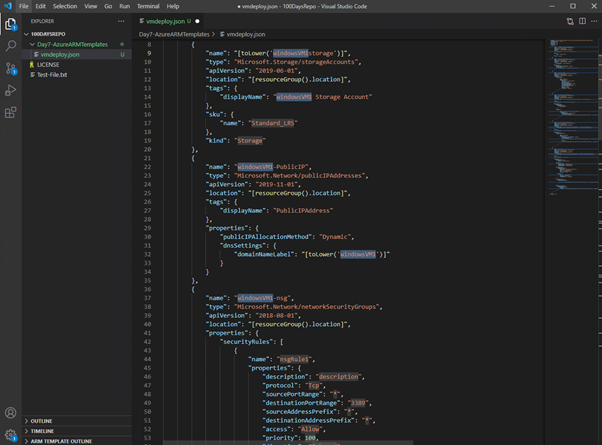

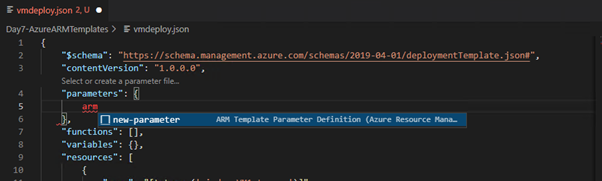

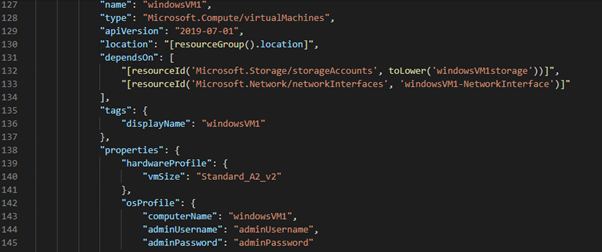

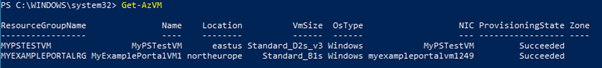

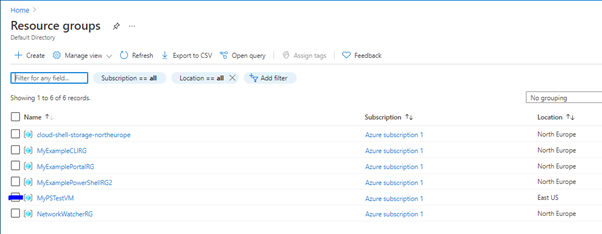

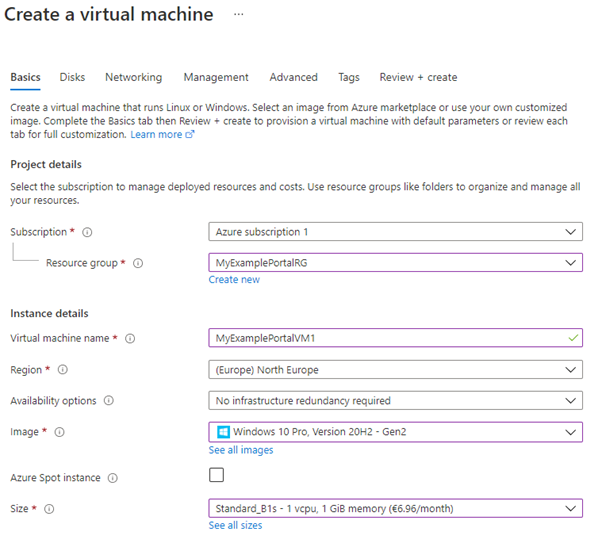

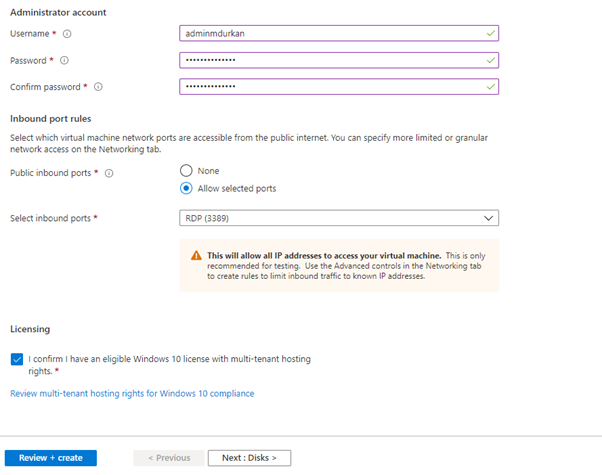

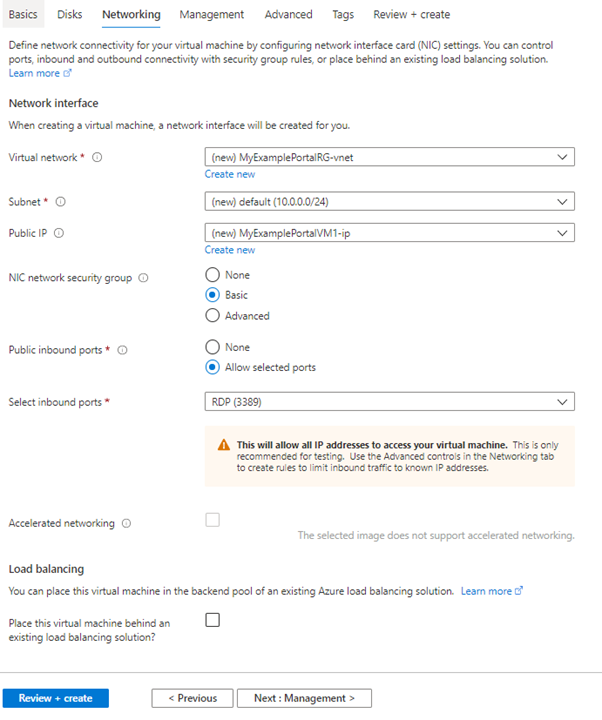

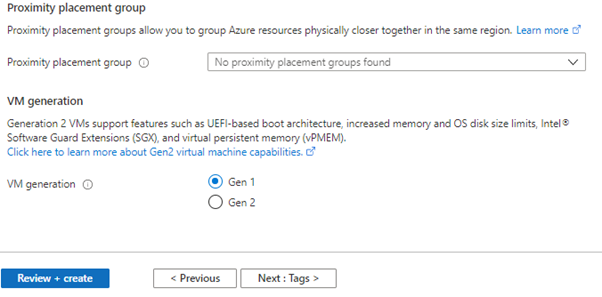

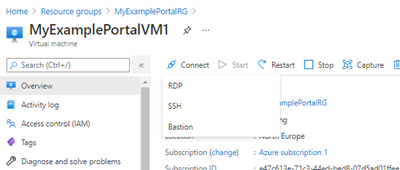

In previous posts, I created Virtual Machines using the Portal, PowerShell and ARM Templates.

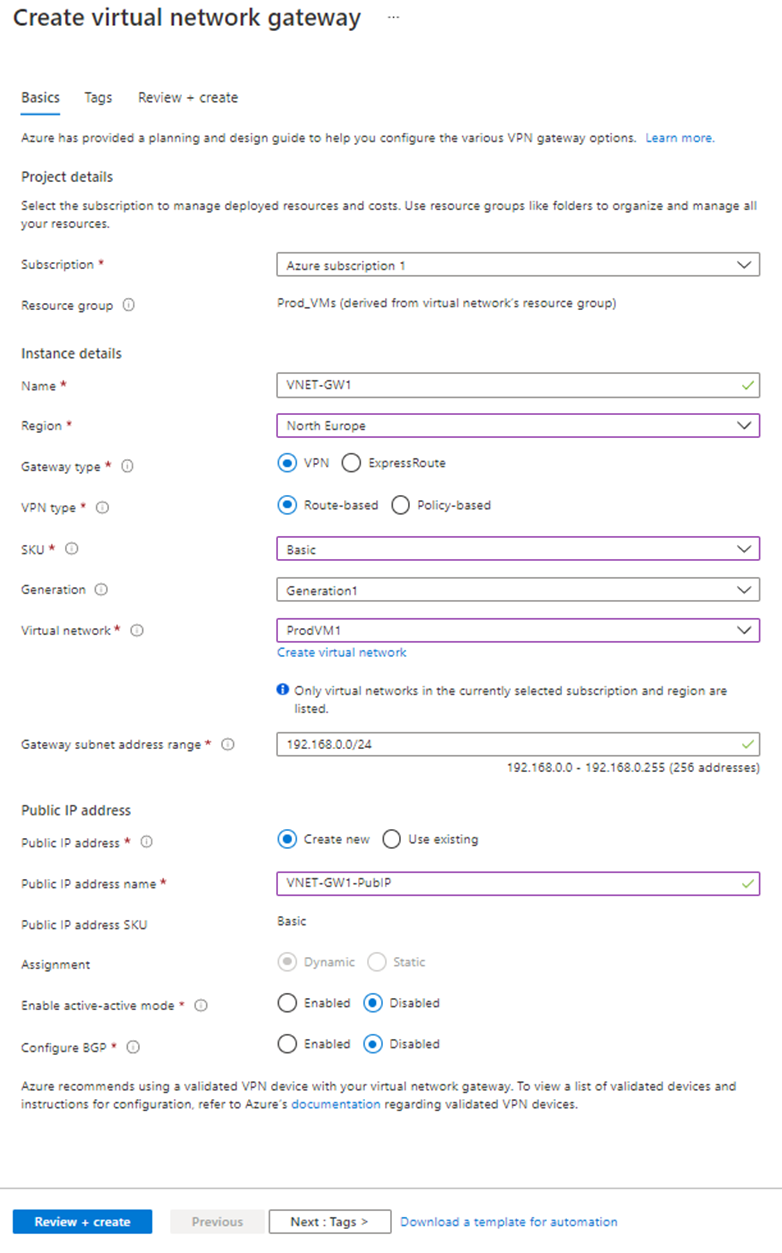

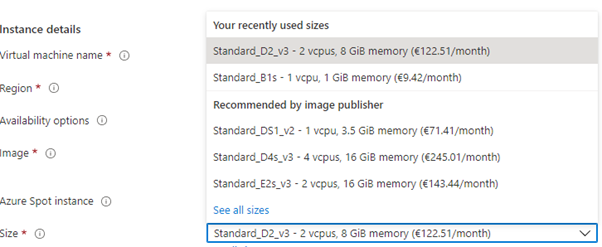

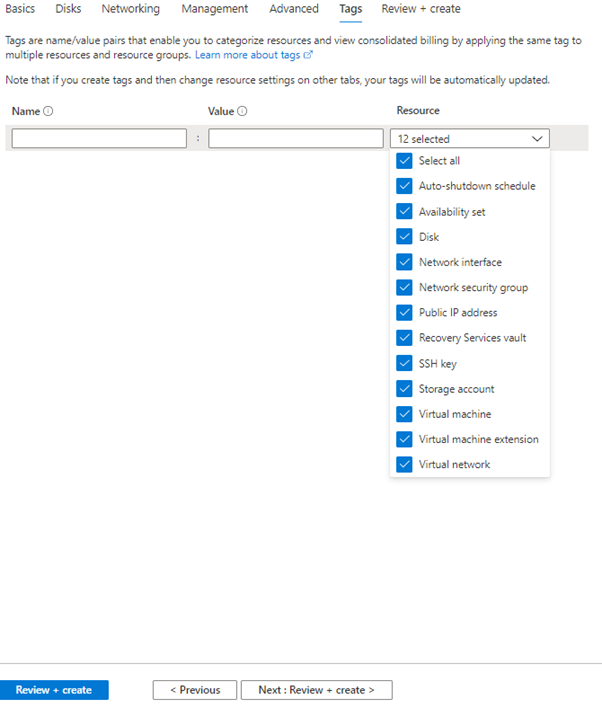

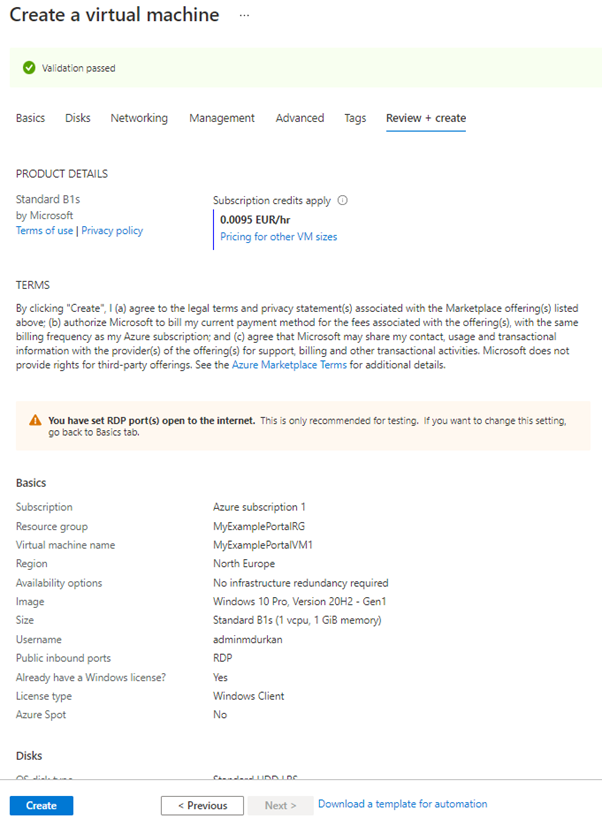

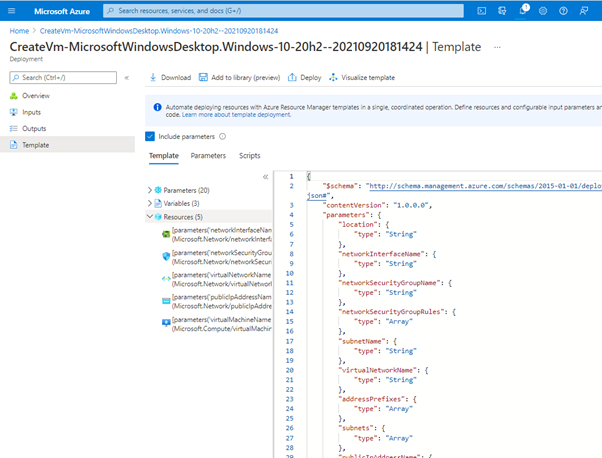

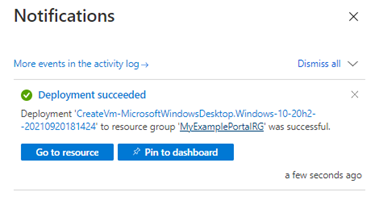

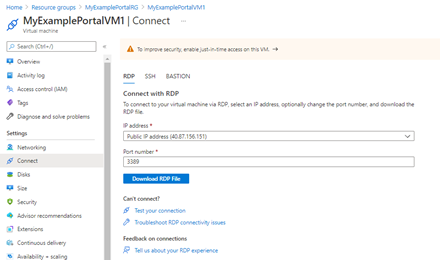

If we jump back to the Portal Method, we can assign a system managed identity in the “Management” tab of the Virtual Machine creation wizard:

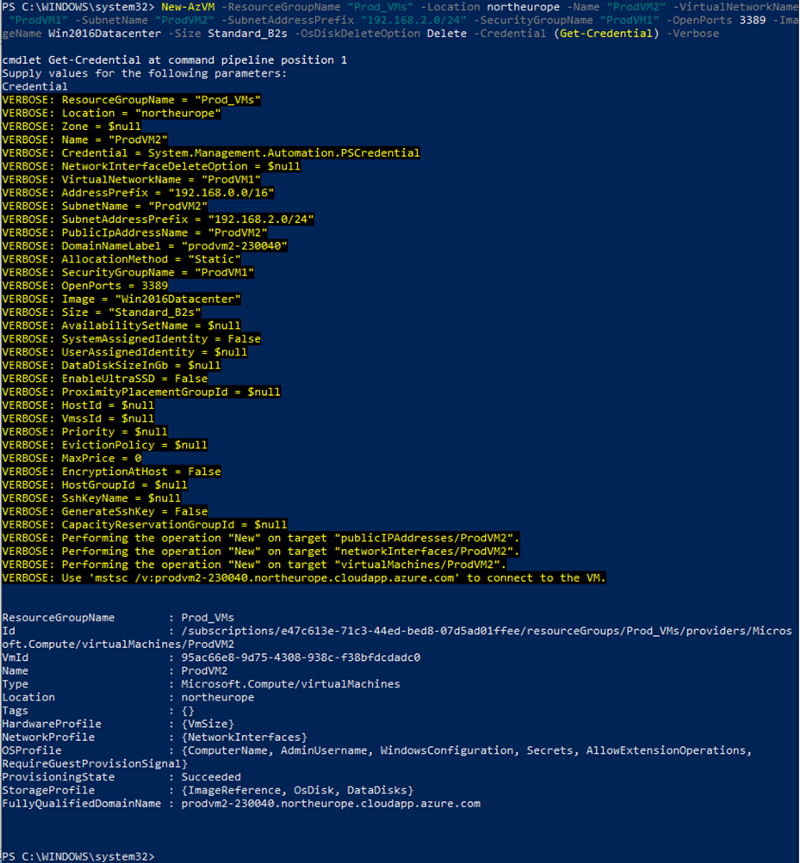

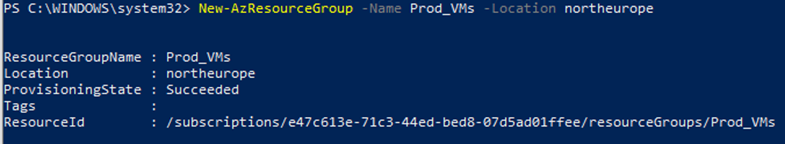

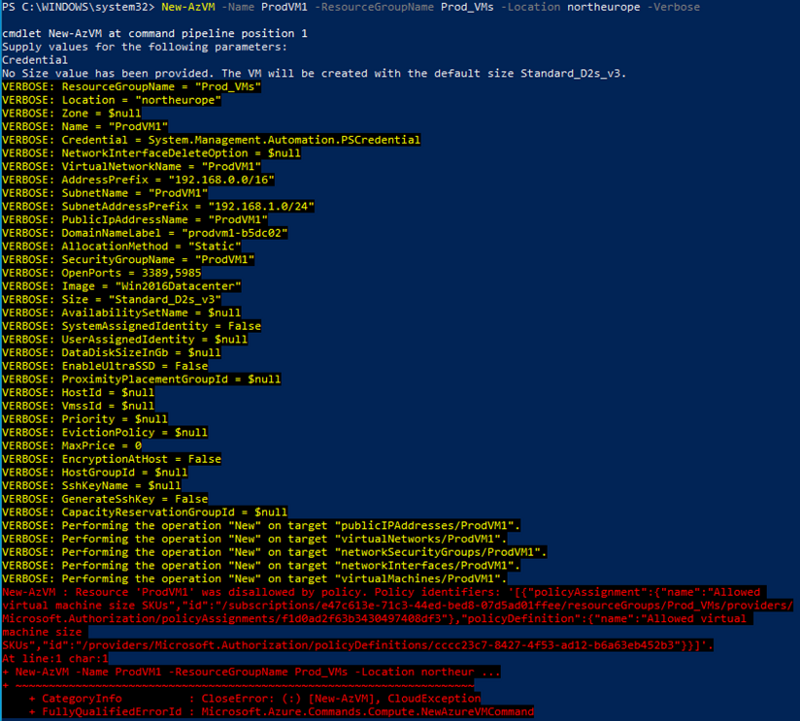

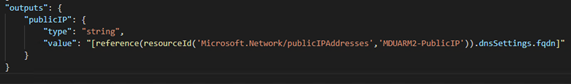

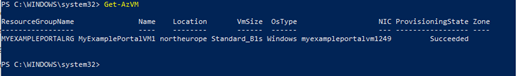

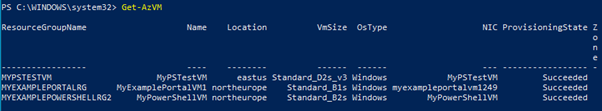

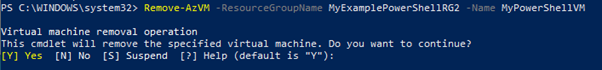

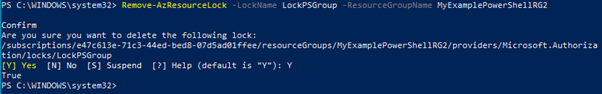

When creating the VM using the Powershell method, I add the “-Verbose” switch to give me the full command output, and I can see the “-SystemAssignedIdentity” parameter is added. However, I don’t add a value, as this tells the command to create the VM with a System Managed Identity

New-AzVM -ResourceGroupName MyExamplePowerShellRG2 -Location northeurope -Name MyPowerShellVM -AddressPrefix “10.30.0.0/16” -SubnetName PSVMSubnet -SubnetAddressPrefix “10.30.30.0/24” -PublicIPAddressName PSPublicIP -DomainNameLabel PSVM001MD -SecurityGroupName PSVMNSG -OpenPorts 3389 -ImageName Win2016Datacenter -Size Standard_B2s -OsDiskDeleteOption Delete -SystemAssignedIdentity -Credential (Get-Credential) –Verbose

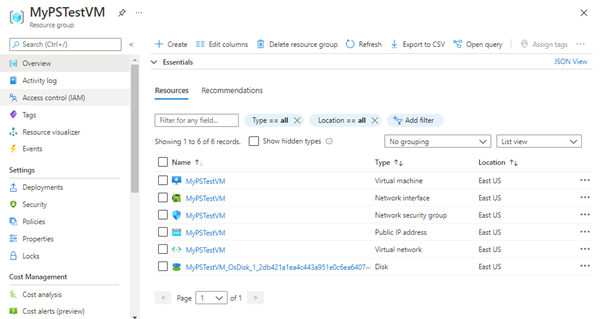

Once my VM gets created, I can see under the “Identity” menu option that the System Managed Identity has been created:

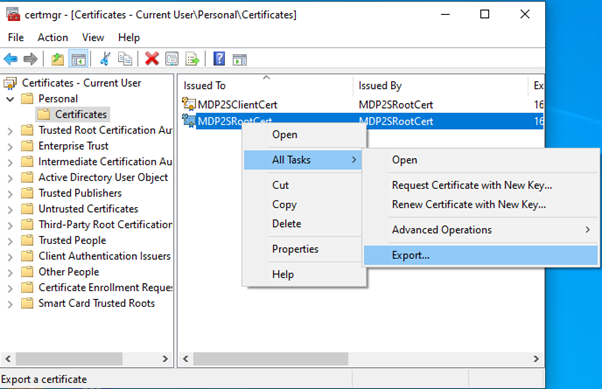

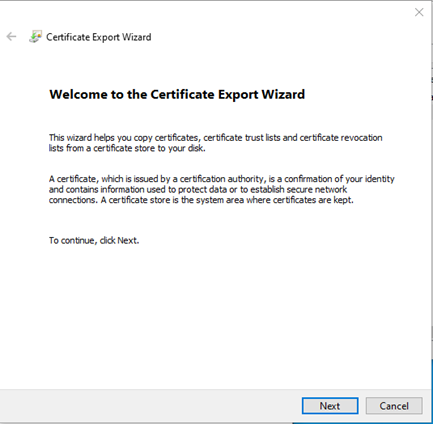

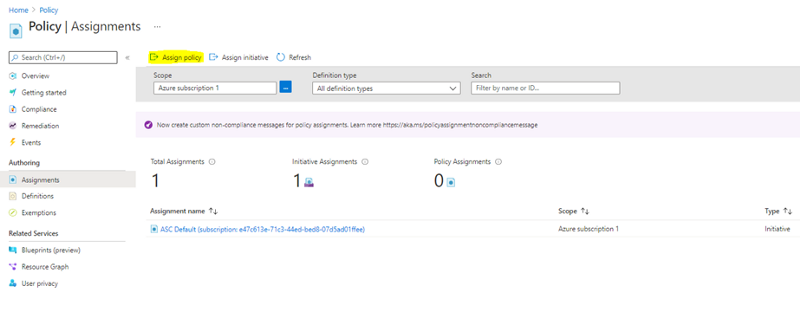

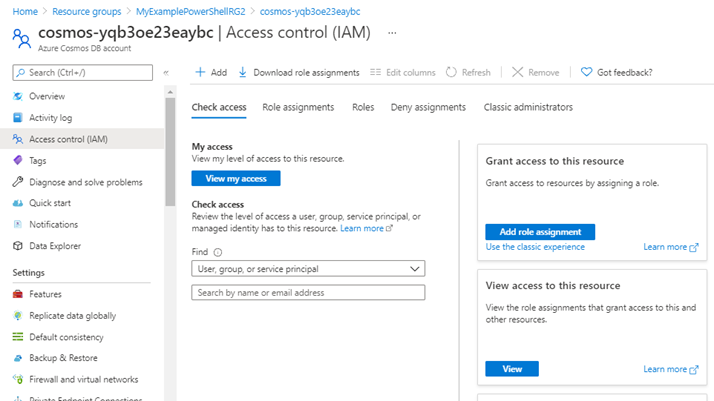

So now we have our identity, we need somewhere to assign it to. For the purposes of this Demo, I’ve created an Azure Cosmos DB. So in the Cosmos DB instance, I go to the “Access Control (IAM)” menu option, and click on “Add Role Assignment”:

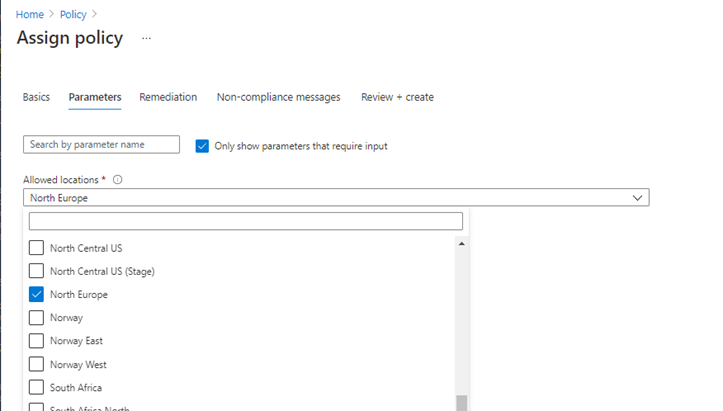

On the “Add Role Assignment” screen, I pick the access level for the role I want to assign:

On the “Members” screen, I can select the Managed Identity that I created on the Virtual Machine:

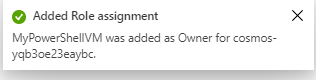

I click “Review and Assign” to confirm the role assignment, and this is then confirmed:

And that is how Managed Identities work in Azure. As you can see, no passwords or credentials are needed. You can view the official Microsoft Docs article on Azure Managed Identities here, which gives a full overview.

Hope you enjoyed this post, until next time!!